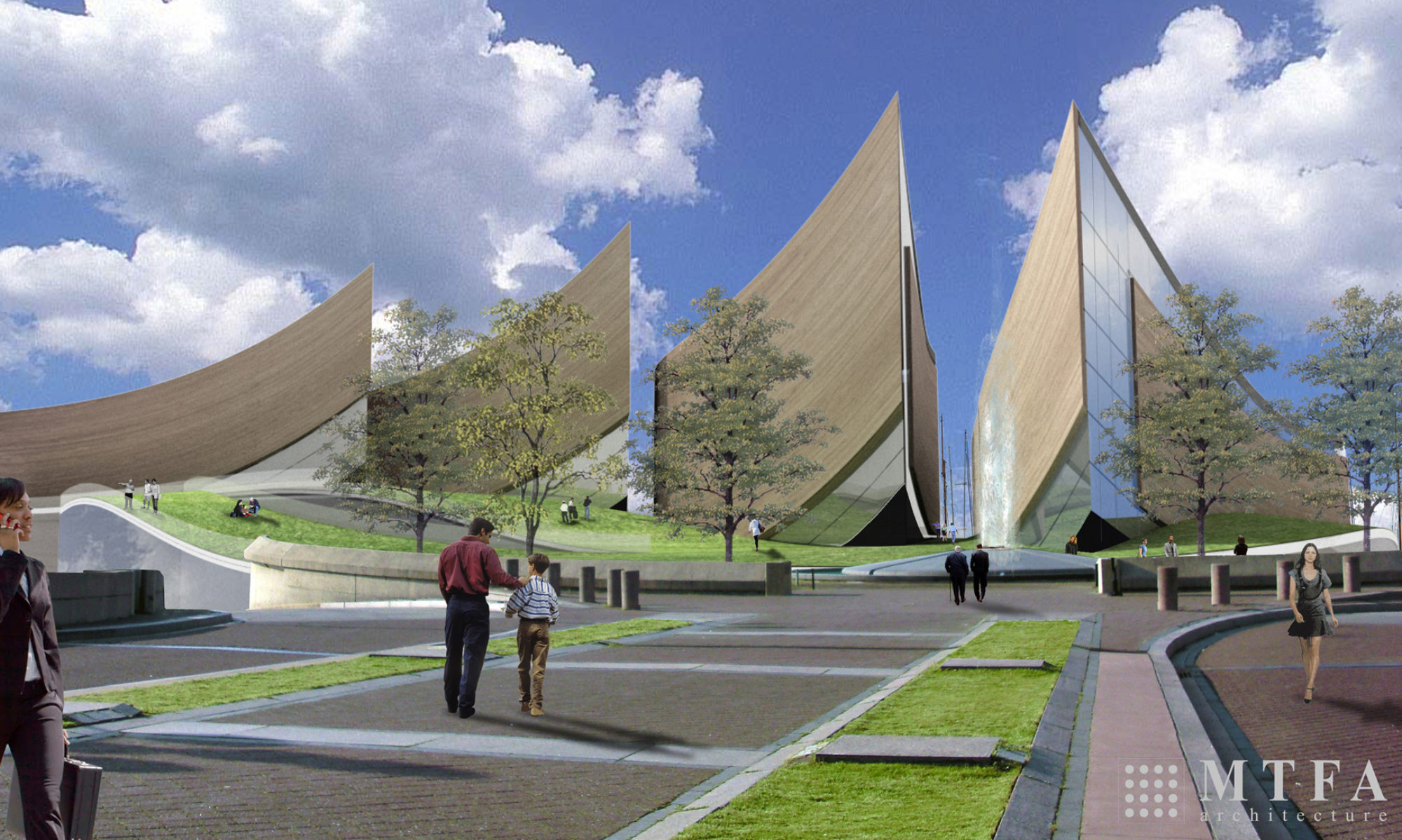

This is the second of four blogs to describe how the National Museum of the American People will tell its story through four chapters.

The second chapter of the story that the National Museum of the American People will tell covers the major settlement groups who came to America from 1607 to 1820 and the consequences of this settlement on the native peoples in what is now the Eastern U.S. The chapter will also focus on the inflow of Western Europeans and Africans in the East, and Hispanics settling in what is now the U.S. Southwest. This chapter is bisected by the American Revolution and creation of the nation.

It will go on to explore the new nation’s westward expansion as it takes in new peoples with the Louisiana Purchase extending the nation to the Mississippi River and the annexation of Florida. The migration within what is now the United States by both settlers and natives will also be covered.

Chapter 2 begins with the first permanent English settlement in Jamestown in 1607. This is generally recognized as the beginning of the Colonial Period. While scholars will provide the essential history of this period, the NMAP will also explore myths and legends about these times, some of which persist.

Europeans in the 18th and 19th centuries, as they pushed west across the continent, reported encountering pristine forests and massive herds of bison and believed that it was always thus. Now, our best evidence suggests that humans settled and dominated most of the land and kept the vegetation and bison in check long before Europeans arrived. In the two hundred years after the near demise of the native population due to disease and government policies, both before and after the nation was formed, the bison population exploded, the land went to seed and “virgin forests” spread.

As visitors walk through this history from 1607 to the adoption of the U.S. Constitution in 1789 they will learn that about 600,000 Europeans who came and 300,000 Africans who were brought to the English colonies. Virtually all of the Africans came as slaves and about half of the Europeans were indentured servants or convicts.

While English immigrants dominated this influx and largely settled in Virginia, Maryland and New England, only a minority, even in New England — even on the Mayflower itself — were Pilgrims and Puritans. While some indeed came to escape religious persecution, most of the English came for economic opportunities. It took about a century before these colonies achieved a self-sustaining population.

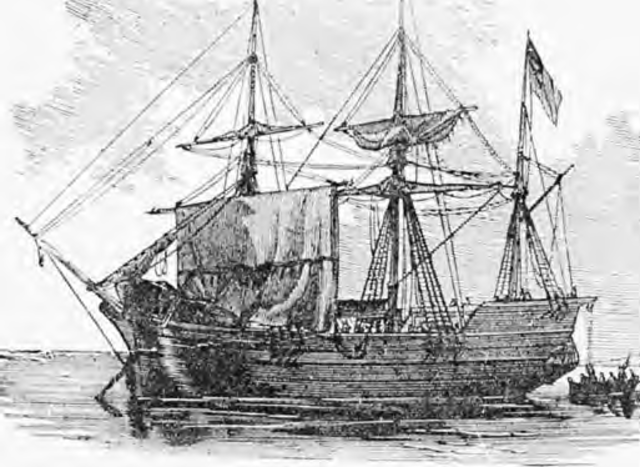

The African slave trade with Europe began in the mid-15th Century, before Columbus’ voyage, with the Spanish and Portuguese importing slaves first to Europe and Atlantic islands and then to Spanish and Portuguese America.

It has been calculated that up to a third of all slaves taken out of Africa died aboard ships as they sailed across what was known as the Middle Passage. An unknown number of lives were also lost in Africa, mostly in a strip about 100 miles wide along the central West Coast, as a result of the slave trade from attempts to capture them and on their journey to ports of embarkation.

More than 10 percent of imported slaves — some 50,000 — came after Congress abolished the slave trade in 1810. Slaves brought to this land are the ancestors of more than 20 million Americans, the second largest group in the nation after German Americans.

This chapter also begins showing an inkling of the great diversity of peoples that will characterize the American people. By 1790 there were significant numbers of Scotch, Irish and German immigrants living side-by-side with the English colonists, with smaller numbers of Dutch, French, Swedish, Spanish and others. Each group added to and influenced the language, culture, economy and politics of the fledgling nation.

The Scotch settled primarily in the Carolinas, Georgia, Virginia, Kentucky and Tennessee. The first Irish immigrants tended toward the middle and southern states. Few Germans went to New England and instead migrated to the middle states, with Pennsylvania getting most of them.

The Dutch went mostly to New York and New Jersey where the early colony of New Amsterdam had been. The French settled almost entirely in the Northwest Territories of modern Canada and on a long and narrow swath that ran from Detroit down the Mississippi River to New Orleans.

The Spanish at this point were in territories in Florida, California and New Mexico. The largest of a small contingent of Swedes was in New Mexico. Jews were scattered throughout the colonies and established outposts in the port cities of New York, Newport, Savannah, Philadelphia and Charleston. Smaller numbers of many other European ethnicities came as well, mixed among other groups.

The National Museum of the American People will show where each group settled and how they contributed to the creation of the nation.

At the heart of this chapter is the story of the creation of the nation. The history about the relationship of the 13 colonies with England, the actions and reactions that led to that relationship souring to the point of being irreconcilable, the American Revolutionary War and the creation of the United States of America will all be told.

Groups that played significant roles in the lead-up to the Revolutionary War, played a major role during the war, and were represented among the Founding Fathers are part of this story. The museum will also explore where the ideas came from for our founding documents: the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, the Federalist Papers and the Constitution.

Facets of this chapter are told in partial ways at a variety of on-site museums and recreated exhibitions such as at Colonial Williamsburg, Jamestown, Plimoth Plantation, Savannah and Charleston. The new National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington tells the story about African slavery in the United States during this period and the new American Revolution Museum in Philadelphia tells the story about that war.

But there are no institutions that tell the full and comprehensive story about this phase of the making of the American people. The National Museum of the American People will be the first to do so.

NOTE: The material herein is based in part on the books 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus by Charles C. Mann and Coming to America: A History of Immigration and Ethnicity in American Life by Roger Daniels. Leading scholars will develop the museum’s story following the establishment of the museum.

This blog is about the proposed National Museum of the American People which is about the making of the American People. The blog will be reporting regularly on a host of NMAP topics, American ethnic group histories, related museums, scholarship centered on the museum’s focus, relevant census and other demographic data, and pertinent political issues. The museum is a work in progress and we welcome thoughtful suggestions.

Sam Eskenazi, Director, Coalition for the National Museum of the American People