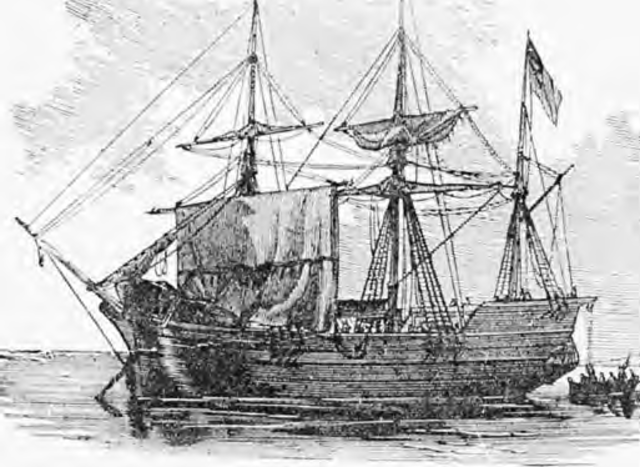

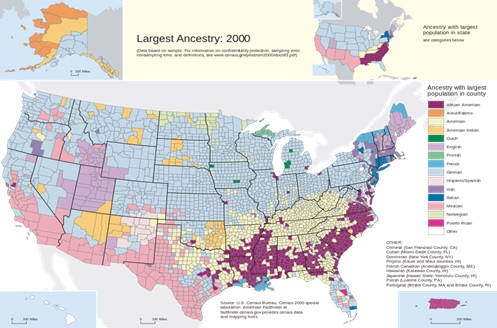

The National Museum of the American People, in telling the story about the making of the American people, will incorporate the story of Hispanic and Latino Americans migrating and immigrating to the U.S. as well as those already on this land when taken over by the U.S.

The 2020 Census found that approximately 19 percent of the U.S. population is comprised of Hispanic or Latino Americans. The Latino population has grown considerably since 1960 when that population was fewer than 6 million, or merely 3.24 percent of the population. Latinos have and will continue to exert an enormous impact on social, cultural, political and economic life in the U.S.

Apart from First Peoples, every American, even if they were born in the U.S., can trace their lineage back to a different part of the world, some more recently than others. The 2020 Census reports that 13.7 percent of the U.S. population was born in another country. My mother and sister are part of that 13.7 percent; I am the first in my family to be born in the U.S. I am proud to be a first-generation Mexican American.

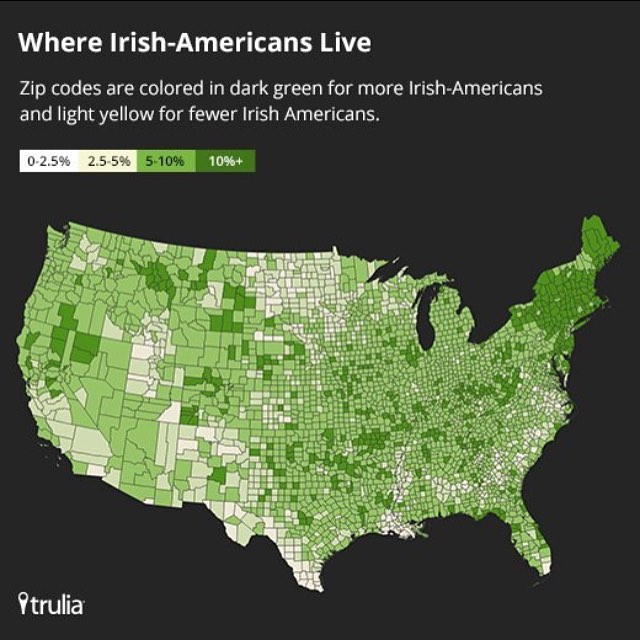

My mom and sister are part of the 25 percent of foreign-born immigrants from Mexico, the largest birthplace of origin for immigrants in the U.S., according to the Pew Research Center. Growing up in an immigrant household, I failed to see my culture and family’s migration story represented in education, pop culture and other areas of American life. To assimilate into the U.S., Latinos should not have to sacrifice any aspect of our culture, and what makes us great as Americans. My mom, sister, and I are strong women who are proud of our heritage, and there are many other Latinas who have paved the way for us to live empowered lives in the U.S.

Sonia Sotomayor’s nomination to the Supreme Court in 2009 gave me the first semblance of hope that I could contribute to my country, honor my ancestors, and find my place in the world. The child of Puerto Rican immigrants, Sotomayor was the first Latina to be confirmed to serve on the Supreme Court. Despite warnings of scrutiny at her confirmation, Sotomayor donned fire-engine red nails and semi-hoop earrings: a symbol of Latina adulthood and pride. Sotomayor’s refusal to sacrifice any aspect of her Latina identity on the bench is inspiring, and reminds Latinas like myself to show up unapologetically everyday. On my first day working at the Department of the Interior last year, I donned fire-engine-red nails – a reminder of those who came before me and to always “echarle ganas” – to always give my best effort in all my endeavors no matter what.

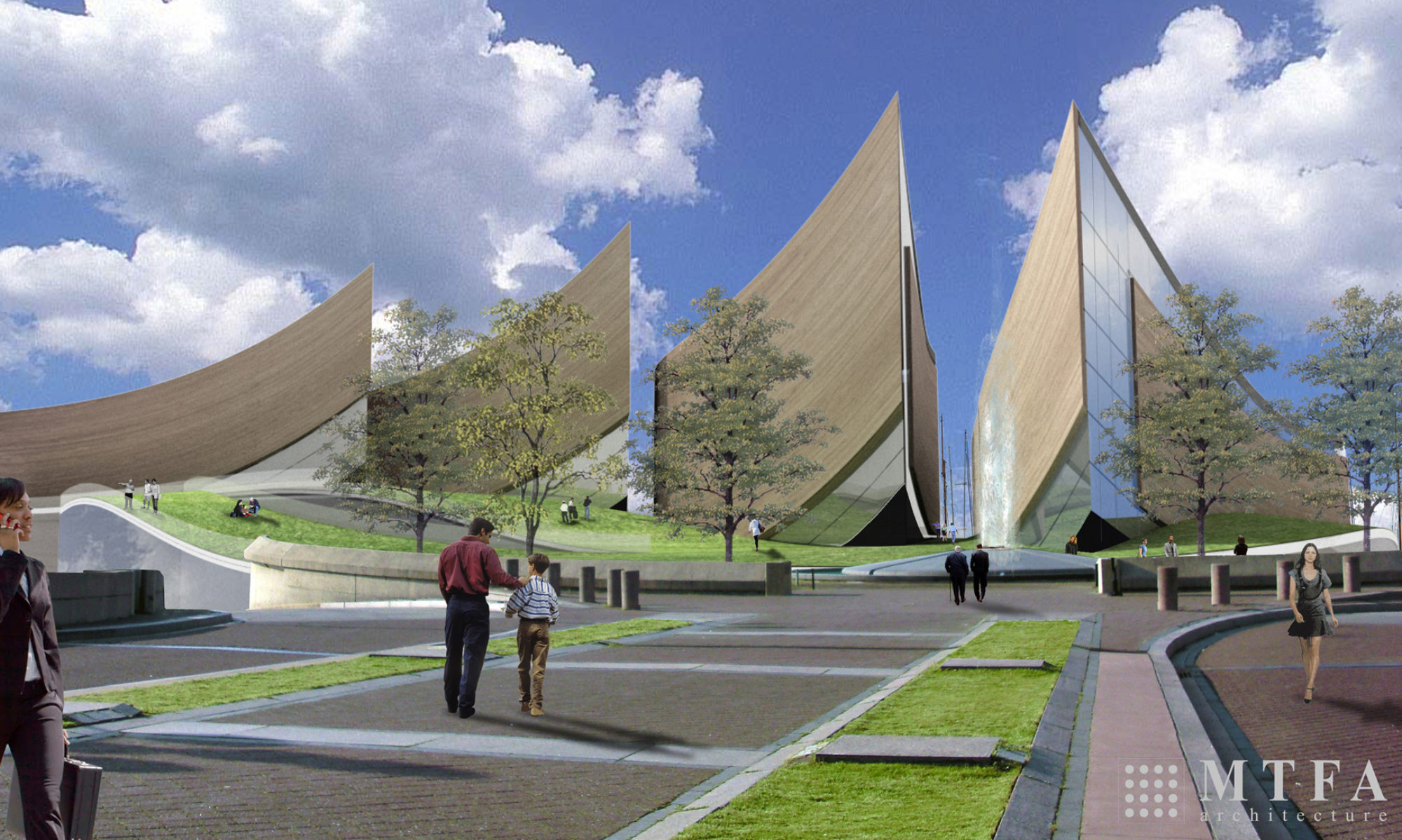

Accurately representing Latino history and culture in popular American spaces like museums matters. Therefore, a museum that will tell the story of all Americans, like the National Museum of the American People, is necessary. The National Museum of the American People will objectively tell the story of Latino immigrants, including Latinas, in all four chapters of the museum’s main exhibit. This museum will foster a sense of belonging to the U.S. by sharing the history of the mosaic of people that have come here and contribute to our national identity, like myself and my family.

—————————-

Sofia Casamassa is graduating from American University this Spring.